Updated November 2021.

*Full reference list available at the conclusion of the resource.

‘The New Testament of Tendons’ aims to provide practitioners and the general population with a comprehensive guide to the management of tendon injury and tendinopathy. It is likely that working as a health practitioner in any capacity that you will be faced with a complex or challenging patient suffering from chronic or acute tendinopathy. For the general population, the majority of individuals with be faced with the management of a tendon injury at some point throughout their lifespan.

Tendinopathy occurs at all stages of the lifespan, accounting for 30-50% of all general practice musculoskeletal consultations.

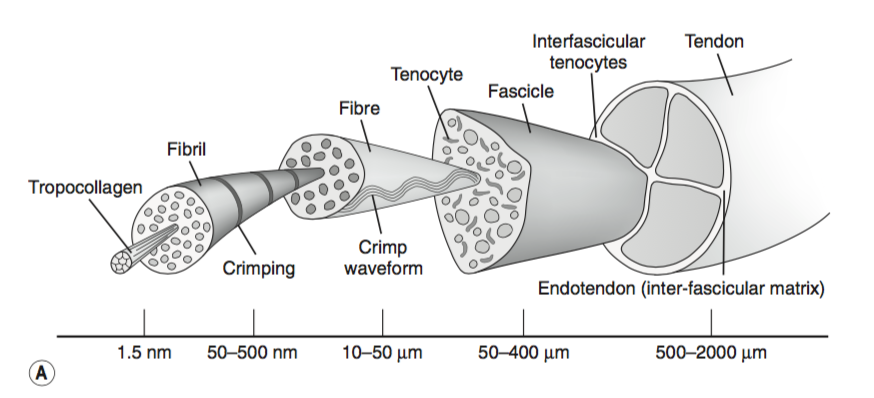

The surrounding structures of the tendon include the fibrous sheath or the retinacula; the synovial sheaths – in tendons lacking a synovial sheath; a peritendinous sheath is located to reduce friction; and lastly the tendon bursae reduces friction at sites where there are boney prominences that may result in the tendon being placed in a compressive position against the bone. Further, the tendon is comprised of the paratenon, epitenon and endotenon providing protective sleeves throughout.

Diving deeper into the tendinous structure; tendons are comprised mostly of type 1 collagen fibers, forming the very basic unit of the tendon. Along with these type 1 collagen fibers elastin is embedded in the proteoglycan- water matrix, these elements are produced by tenocytes and tenoblasts. The endotenon encases and binds each collagen fiber together.

The tendon structure is hierarchical beginning with a group of collagen fibers known as the subfascicle, the group of subfascicles forms a secondary fiber bundle known as a fascicle, progressing into a tertiary bundle which is encased in the epitenon.

Tendons are metabolically active tissues, it is the metabolic activity of the tendon that allows for adaptation of the tendon to occur. The muscle and tendon network are widely known to respond to changes in physical activity, while during periods of immobilisation, a decrease in collagen synthesis is observed. Suggesting, that during periods of physical activity the biosynthesis of the collagen network decreases due to the reduced tensile load on the musculotendinous unit.

The rate of collagen synthesis, however depends largely on the overall protein balance of the tissue. Acute exercise has been observed to induce metabolic and inflammatory changes within the tendon as well as stimulate the synthesis of type 1 collagen, resulting in adaptive changes.

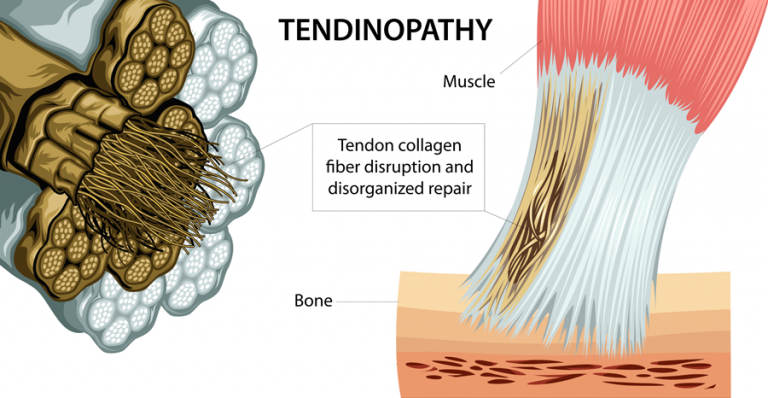

Tendon healing takes place in three phases, inflammation, repair and remodelling. The inflammatory process occurs 3-7 days after the initial injury. Healing cells move into the peritendinous tissue and fascicles while migrating fibroblasts are arranged in relation to the direction of the tissue. It is at approximately day 5 post injury that collagen synthesis begins.

Over the following five weeks, collagen is synthesised continuously with a noticed increase in the generation of fibroblasts within the tendon. In the following months, this new tissue then matures as the collagen fibres settle in the tendon. Type 1 collagen fibers become mechanically stronger and stable in the final repair stage.

Tendinopathy is used to describe the clinical condition of pain and dysfunction of the tendon independent of the pathology. Tendinopathy is often used interchangeably with the term tendinosis, however, tendinosis more accurately describes degenerative changes in the structure.

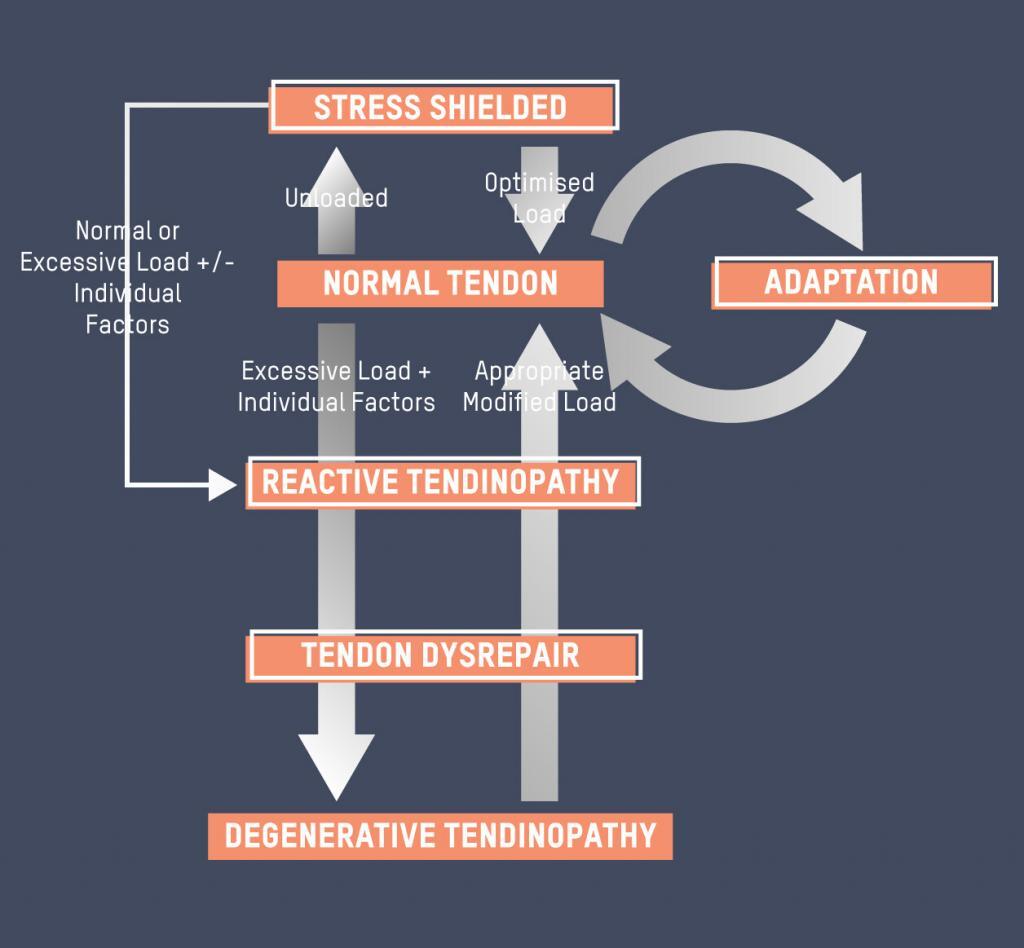

Cook and Purdem (2009) proposed that tendon pathology exists on a continuum with three main phases; reactive tendon, tendon dysrepair and degenerative tendon, this is explained visually below.

Commonly occur acutely and often in younger populations, for example when there is a sudden spike in jumping load the athlete might experience an acute

Is observed in chronically overloaded tendons, often these tendons are thick and have some localised change. Importantly, the frequency, volume and length of time which loads may have a significant impact. There is some evidence to suggest that this can be reversed.

Are typically seen in the older person, for example a recreational runner with focal changes in the achilles, often these injuries are reoccurring but resolve with load monitoring and change each time. There is significant variability of the tendon in this stage with areas of normal and healthy tendon dispersed with patches of degenerated tendon present.

Further the continuum identifies that in the early stages of tendinopathy load management and control of aggravating factors will allow for adaptation of the tendon cells resulting in decreased pain and symptoms as well as increased load tolerance. This new load will become the load that the tendon can best tolerate, before further overload and adaptation take place. It should be noted that it is normal for the tendon to demonstrate changes in the loading process, leading to strengthening of the tendon and an adaptation to the stressors it is placed under.

Cook & Purdum, (2009)

There are many, many factors that contribute to the development of tendinopathy and tendon injuries. Repetitively high loads and forces, overuse, underuse and steroid based medications have been associated with tendon injury and damage, while intrinsic factors including autoimmune conditions, rheumatic conditions, endocrine and metabolic disorders can increase the risk of attaining a tendon injury. Some of the key factors are discussed in detail below:

In children, injuries to the insertion of the tendon are more common than those to the main body, these include Osgood-Schlatter lesions of the knee and Sever’s Disease of the heel. In older populations, overuse injuries of the Achilles tendon and rotator cuff are more common.

Males generally are at a greater risk of tendon injuries than females. However, gluteal tendinopathy is more commonly observed in females due to the biomechanical differences at the hip.

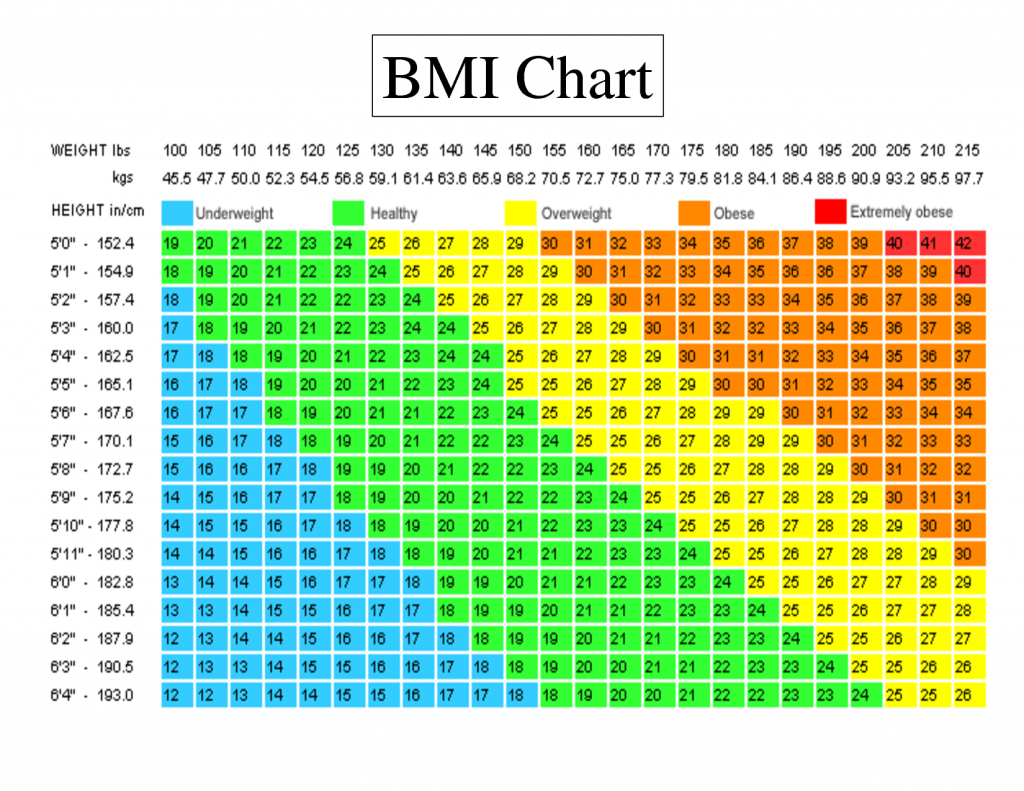

Research suggests that a relationship exists between tendon injury and high levels of body fat. It is thought that a higher BMI results in lower limb tendons in particular being exposed to greater amounts of load, resulting in tendinopathy. From a systemic perspective, it is hypothesised that excess body fat and metabolic alterations have a significant influence on the tendon structure.

Excess training volume, too much tendon load and changes in training volume have been associated with the onset of athletic tendinopathy this may include transition from pre-season training to in season games; change in footwear (eg running shoes to spikes or football boots) or increasing running mileage too quickly. In the general population introducing new exercise (eg: walking); increasing the intensity or duration of the exercise (walking to running or addition of hills); or simply changes in the frequency of the training routine.

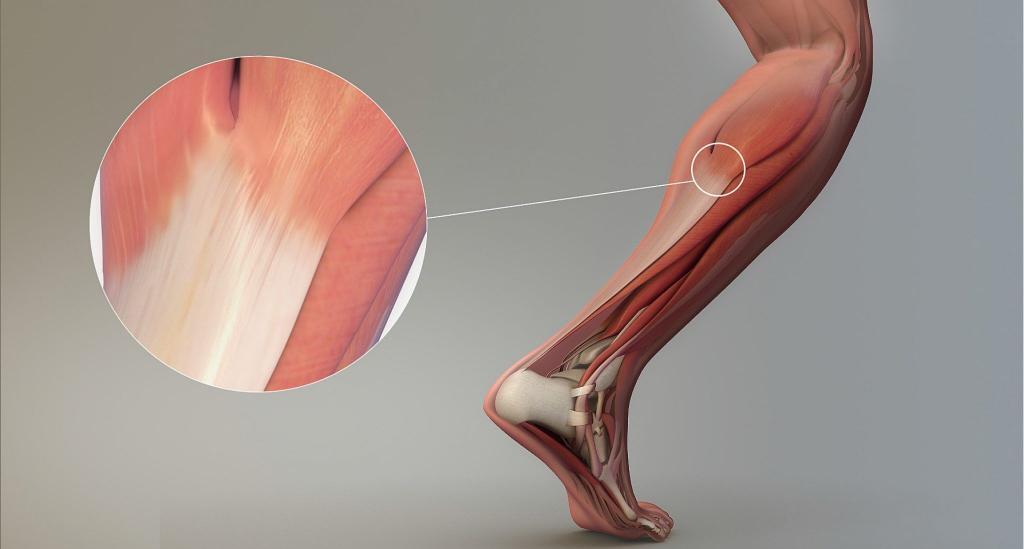

Achilles tendinopathy is characterised by pain and swelling around the Achilles tendon. There are two common types of achilles tendon injuries insertional Achilles Tendinopathy and midportion Achilles tendinopathy. These injuries occur at different locations as described by their name.

About 50% of middle and long distance veteran runners have had complaints of symptoms of Achilles tendinopathy in their lifetime.

• Pain that occurs in Achilles tendinopathy is common at the beginning and end of sessions with a period of relief throughout the training session;

• As the pathology progresses, it is likely that pain will interfere with training, exercise and activities of daily living.

• Posterior ankle impingement

• Sural nerve symptoms and referred spinal pain;

• Stress reactions or fractures and/or bone injury

Colloquially known as “Jumper’s Knee” patella tendinopathy is characterised by localised pain at the front of the knee and is very common in individuals participating in court sports including basketball, hockey, football and jumping athletic events just as high jump and triple jump. Further,patella tendinopathy has been found to commonly occur in runners of all ages. Patella tendinopathy occurs when there is increased load and when there is a high demand on the knee extensor muscle group including the quadricep muscle group.

• Pain at the front of the knee, or the inferior pole of the patella.

• Pain can be aggravated with prolonged sitting, squatting and stair climbing.

• Patella tendinopathy tends to “warm-up” with a reduction in pain as the exercise continues however, is often worse the next day especially following jumping and running activities.

• Pain instantly occurs with high loading activities (eg: jumping).

• Examination of the lower extremity often reveals strength deficits at the hip, knee, ankle and foot.

• Atrophy or reduced strength in lower limb, including gluteus maximus, quadriceps and calf.

• Deficits in energy-storage activities can be assessed through jumping and hopping activities.

Gluteal tendinopathy is characterised by pain around the lateral hip and thigh and has the potential to radiate down into the thigh.

• Commonly occurs in mid-life with females more commonly affected than females.

• There are reports of 23.5% of women being affected by gluteal tendinopathy oppose to 8.5% of men between the ages of 50-79 years.

• Pain and tenderness around the greater trochanter with some radiation down the thigh.

• Onset of pain is often insidious and worsens over time.

• Pain is often associated with changes to the training load or physical activity – for example increased hill walking.

• Symptoms can occur during a slip of fall where there is a strong contraction of the abductor muscles.

• Pain is often worse at night, which is also one of the last symptoms to dicipate.

• Single leg balance tasks (eg: dressing; stair climbing and rising from sitting to standing) can result in an aggravation of symptoms.

Proximal hamstring tendinopathy is characterised by pain deep in the hamstring. Pain occurs at the attachment site to the ischial tuberosity, inferior to the gluteal muscles. Proximal hamstring tendinopathy commonly occurs in distance runners and athletes performing change of direction activities such as footballers and hockey players.

Proximal hamstring tendinopathy also occurs in the general population. Causes of proximal hamstring tendinopathy are common amongst other tendinopathies including training errors (increased volume and/or intensity) often with the introduction of sprinting and lunging.

• Pain with sitting, lunging or squatting – positions where the proximal hamstring attachment is placed in a compressed position around the ischial tuberosity.

• Symptoms may also be aggravated by the use of static hamstring stretches and end range hip flexion.

Pain can also come from other sources including;

• Sciatic nerve irritation

• Ischiofemoral impingement

• Deep gluteal muscle tear

• Posterior pubic or ischial ramus stress fracture

As is observed in other clinical presentations, for example low back pain, the imaging of tendons is limited in the clinical setting. It has been identified that imaging findings do not directly correlate to symptom presentation and does not represent the clinical picture. Imaging including ultrasound or MRI allow for structure visualisation and may be helpful in determining a differential diagnosis.

The role of NSAIDs is to inhibit tissue inflammation and reduce proinflammatory prostaglandin synthesis. It has been identified that NSAIDs may provide symptomatic relief, allowing the individual to continue to ignore symptoms, however, this may delay the healing process and result in further damage.

Despite reducing symptoms and providing some pain releif NSAIDs are unlikely to result in sustained improvement and healing of the injured tendon, further there is no biologic basis for the use of NSAIDs in tendinopathy due to the absence of a true inflammatory process.

Local corticosteroid injections are often used to reduce the inflammatory response in individuals with tendinopathies. However, it is important to note that inflammation is not always a key feature observed in tendinopathy and the use of corticosteroids may in fact inhibit the healing process.

Further, studies have identified that intratendinous corticosteroids can negatively affect the mechanical properties of the tendon, leading to weakening of the tendon and potential rupture, particularly in load bearing tendons. Additionally a 2009 study identified that corticosteroids had similar outcomes in the initial phases of rehabilitation to heavy slow resistance training (HSR) and eccentric training (ECC) however, the clinical improvement was reduced after 12 weeks.

Despite reducing symptoms and providing some pain releif NSAIDs are unlikely to result in sustained improvement and healing of the injured tendon. Further, there is no biologic basis for the use of NSAIDs in tendinopathy due to the absence of a true inflammatory process.

As with many other conditions the first goal of treatment should be to reduce pain. For tendinopathy this usually involves removing the provocative load as well as reducing any high, energy storage activities that are causing the pain. For example, in Achilles tendinopathy this could be reducing the tendons exposure to compressive load (ie: dorsi-flexion) and in the patella tendon this would include reducing activities including maximal jumping and hopping.

The intention is to re-introduce this load in a controlled manner using pain monitoring techniques to assist. Rehabilitation should involve the whole kinetic chain and progress to include these high energy storage activities to increase the load capacity of that tendon – e.g. the patella tendon in jumping and hopping activities.

Shockwave therapy (extracorporal shockwave therapy), a non-invasive treatment technique, has been used on chronic tendinopathies for several decades. Traditionally used in the treatment and management of kidney stones there is more evidence emerging for the use of shockwave therapy in tendinopathies.

The exact mechanism of shockwave therapy is not clearly understood, however it is thought to have an analgesic effect and an effect on the regeneration of new tissue which may be beneficial in the treatment of tendinopathy. This is an emerging treatment method and more research is required.

Physical and manual therapies could act as an adjunct to load management and exercise therapy to assist in increasing joint range of movement, flexibility and mobility.

Platelets have a demonstrated role in the healing process specifically in coagulation, inflammatory processes and immunity modulation. Platelet Rich Plasma or PRP has been suggested as an alternative method for treating tendinopathies. PRP is thought to promote the natural healing process of the tendon.

The evidence however, for the use of PRP in the treatment of tendinopathy is limited with many studies producing conflicting outcomes. This form of treatment requires further research largely due to the clinical diversity observed in the management of tendon pain and tendinopathy.

The biologic tissues within the tendon have the unique capacity to adapt over time and to increase the load tolerance and ability to absorb energy transfer. Due to these remodelling capabilities of tendons within the human body exercise loading programs have demonstrated to be beneficial in the management of tendinopathy.

As discussed earlier, the metabolic capabilities of the tendon mean that when acute load is applied to the tendon there is an inflammatory response the elicits positive change within the tendon. Further, exercise load assists in restoring the stiffness of the pathological tendon improving the function of the tendon and decreases the risk of injury. In tendons, periods of rest tend to lead to further reductions in load tolerance, increasing the risk of tendon injury.

Isometric exercises have been used to reduce and manage tendon pain as well as initiate loading of the musculotendinous unit. This has been demonstrated in patella tendinopathy, where the completion of isometric quadricep exercises has been demonstrated to achieve a reduction in the motor cortex inhibition of the quadriceps muscles which has previously been observed in tendinopathy.

Rio et al, prescribed a dose of 5 x 45 seconds at 70% of maximal muscle contraction which was shown to reduce patella tendon pain, however this finding has the potential to be applied to other lower limb tendons including gluteus medius, hamstring and Achilles tendons. The use of isometric exercises can be useful clinically as a prognostic tool for tendinopathy.

Eccentric loading of the tendon revolves around the isolated, slow-lengthening muscle contraction. It is thought that eccentric loads may inhibit the blood flow into the tendon and alter the nociceptive input, potentially having a secondary effect on the pain response and altering the ability to increase the load on the tendon.

It is also thought that the pain production associated with eccentric training for a pathological tendon could change the reflex drive to the lower limb muscles.

HSR involves participants completing a 12 week program where the load of the exercises is gradually increased while the repetitions are decreased. The repetition and loads are described as: 3 times, 15-repetition maximum (15RM), in week 1; 3 times, 12RM, in weeks 2 to 3; 4 times, 10RM, in weeks 4 to 5; 4 times, 8RM, in weeks 6 to 8; and 4 times, 6RM, in weeks 9 to 12.

The exercises were performed through full range of motion with the eccentric and concentric phases being completed for 3 seconds each. In this protocol, as with the previously mentioned treatment options, pain during the exercise is acceptable but was not to increase the following day.

The findings suggest that HSR is effective in normalising tendon tissue when compared to eccentric training and can have good clinical outcomes. HSR has been further demonstrated to have positive clinical effects in the short term and the long term as well as improvements in tissue pathology and collagen turnover.

It is evident from the above information that all of the loading programs have a beneficial outcome in pathological tendons. However, the evidence suggests isometric training in the short term may be beneficial to immediately reduce tendon pain for at least 45 minutes after the intervention.

Once able, within pain limitations it would be reasonable to assume that an eccentric-concentric heavy and slow resistance training program would be appropriate as a means to address strength deficits. Prior to the return to sport and at practitioner discretion an energy-storage program should be followed to increase the load tolerance of the aggravated tendon.

Further at return to sport, the patient should be able to meet the demands of the sport with minimal pain. Pain should be monitored for the 24 hours following a loading protocol, an increase in pain suggests that the loads given were too great and should be adjusted accordingly.

Compressive loads have also been demonstrated to be a problematic for tendons. Compressive load occurs when the tendon is placed in a position where it is pressed against the boney prominence or attachment.

For example when stretching the hamstring in a supine position with the leg extended in the air the insertional hamstring tendon is placed in a position of compression against the ischial tuberosity, likewise for the Achilles tendon when the foot is placed in a dorsiflexed position and the patella tendon when squatting or stair climbing.

Stretching should be used at the discretion of the practitioner at an appropriate time point in the rehabilitation program.

The use of ice results in the decrease in tissue temperature, pain, swelling and muscle spasm. At a cellular level, the use of cold or cryotherapy results in reduced cellular metabolism, inflammation, tissue extensibility and joint proprioception.

Cold therapy has been demonstrated to have an impact at the cutaneus level, however has not been demonstrated to penetrate deeper than 2cm below the skins surface. While there is evidence to suggest that ice can decrease the inflammatory response and cellular to an acute injury less is known about the use in tendinopathy.

It is important to note, as with NSAIDs, that a reduction in the inflammatory processes and cellular metabolism may actually result in a slowed or delayed healing process. There is also a lack of evidence supporting the use of heat in the treatment and management of tendinopathy. There is evidence to suggest that with the application of heat there may be changes in the tissue extensibility with increases in the thermal bond strength after tendon repair.

• A sudden or acute increase in training load, frequency or duration;

• Decreased recovery periods between training sessions;

• Poor flexibility;

• Decreased joint range of movement.

• Localised pain;

• Pain that worsens as load increases (eg: low level or no pain with calf raises, but pain is worsened with hopping; or no pain with walking, however pain increases with running);

• Pain and/or stiffness around the joint, especially when waking in the morning or after periods of rest;

• Swelling or thickening of the tendon.

1. Increase training or exercise loads gradually – tendon’s do not like surprises;

2. Avoid changing too many training or exercise factors in one go;

3. Participate in a strength training program that focuses on whole body strength to ensure the body is tolerant to changes in exercise load.

Do you need help from an Exercise Physiologist?

Challoumas D, Clifford C, Kirwan P, et al., How does surgery compare to sham surgery or physiotherapy as a treatment for tendinopathy? A systematic review of randomised trials BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2019;5

Kannus P. Structure of the tendon connective tissue. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 2000 Dec;10(6):312-20.

Kjaer M, Langberg H, Miller BF, Boushel R, Crameri R, Koskinen S, Heinemeier K, Olesen JL, Dossing S, Hansen M, Pedersen SG. Metabolic activity and collagen turnover in human tendon in response to physical activity. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2005 Mar;5(1):41-52.

Lin TW, Cardenas L, Soslowsky LJ. Biomechanics of tendon injury and repair. Journal of biomechanics. 2004 Jun 1;37(6):865-77.

Malliaras P, Kamal B, Nowell A, Farley T, Dhamu H, Simpson V, Morrissey D, Langberg H, Maffulli N, Reeves ND. Patellar tendon adaptation in relation to load-intensity and contraction type. Journal of biomechanics. 2013 Jul 26;46(11):1893-9.

Tardioli A, Malliaras P, Maffulli N. Immediate and short-term effects of exercise on tendon structure: biochemical, biomechanical and imaging responses. British medical bulletin. 2012 Jan 25;103(1):169-202. Maffulli N, Moller HD, Evans CHTendon healing: can it be optimised?British Journal of Sports Medicine 2002;36:315-316.

Cook JL, Purdam CR. Is tendon pathology a continuum? A pathology model to explain the clinical presentation of loadinduce tendinopathy. British journal of sports medicine. 2009 Jun 1;43(6):409-16.

Maffulli N, Wong J, Almekinders LC. Types and epidemiology of tendinopathy. Clinics in sports medicine. 2003 Oct 1;22(4):675-92.

Gaida JE, Ashe MC, Bass SL, Cook JL. Is adiposity an under‐recognized risk factor for tendinopathy? A systematic review. Arthritis Care & Research: Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology. 2009 Jun 15;61(6):840-9.

Cook JL, Purdam C. Is compressive load a factor in the development of tendinopathy?. Br J Sports Med. 2012 Mar 1;46(3):163-8.

Shaikh Z, Perry M, Morrissey D, Ahmad M, Del Buono A, Maffulli N. Achilles tendinopathy in club runners. International journal of sports medicine. 2012 May;33(05):390-4.

Cook JL, Khan KM, Purdam C. Achilles tendinopathy. Manual therapy. 2002 Aug 1;7(3):121-30.l.

Maffulli N, Sharma P, Luscombe KL. Achilles tendinopathy: aetiology and management. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2004 Oct;97(10):472-6.

Malliaras P, Cook J, Purdam C, Rio E. Patellar tendinopathy: clinical diagnosis, load management, and advice for challenging case presentations. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2015 Nov;45(11):887-98.

Grimaldi A, Mellor R, Hodges P, Bennell K, Wajswelner H, Vicenzino B. Gluteal tendinopathy: a review of mechanisms, assessment and management. Sports Medicine. 2015 Aug 1;45(8):1107-19.

Goom TS, Malliaras P, Reiman MP, Purdam CR. Proximal hamstring tendinopathy: clinical aspects of assessment and management. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2016 Jun;46(6):483-93.

Docking SI, Ooi CC, Connell D. Tendinopathy: is imaging telling us the entire story?. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2015 Nov;45(11):842-52.

Magra M, Maffulli N. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in tendinopathy: friend or foe. Kongsgaard M, Kovanen V, Aagaard P, Doessing S, Hansen P, Laursen AH, Kaldau NC, Kjaer M, Magnusson SP. Corticosteroid injections, eccentric decline squat training and heavy slow resistance training in patellar tendinopathy. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 2009 Dec;19(6):790-802.

Speed CA. Corticosteroid injections in tendon lesions. Bmj. 2001 Aug 18;323(7309):382-6. Malliaras P, Cook J, Purdam C, Rio E. Patellar tendinopathy: clinical diagnosis, load management, and advice for challenging case presentations. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2015 Nov;45(11):887-98.

van Leeuwen MT, Zwerver J, van den Akker-Scheek I. Extracorporeal shockwave therapy for patellar tendinopathy: a review of the literature. British journal of sports medicine. 2009 Mar 1;43(3):163-8.

Andia I, Latorre PM, Gomez MC, Burgos-Alonso N, Abate M, Maffulli N. Platelet-rich plasma in the conservative treatment of painful tendinopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled studies. British medical bulletin. 2014 Jun 1;110(1).

Mautner K, Colberg RE, Malanga G, Borg-Stein JP, Harmon KG, Dharamsi AS, Chu S, Homer P. Outcomes after ultrasoundguided platelet-rich plasma injections for chronic tendinopathy: a multicenter, retrospective review. PM&R. 2013 Mar 1;5(3):169-75.

Malliaras P, Cook J, Purdam C, Rio E. Patellar tendinopathy: clinical diagnosis, load management, and advice for challenging case presentations. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2015 Nov;45(11):887-98.

Allison GT, Purdam C. Eccentric loading for Achilles tendinopathy—strengthening or stretching?. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2009 Apr 1;43(4):276-9.

Kongsgaard M, Kovanen V, Aagaard P, Doessing S, Hansen P, Laursen AH, Kaldau NC, Kjaer M, Magnusson SP. Corticosteroid injections, eccentric decline squat training and heavy slow resistance training in patellar tendinopathy. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 2009 Dec;19(6):790-802.

Malliaras P, Cook J, Purdam C, Rio E. Patellar tendinopathy: clinical diagnosis, load management, and advice for challenging case presentations. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2015 Nov;45(11):887-98.

Leadbetter JD. The effect of therapeutic modalities on tendinopathy. InTendon Injuries 2005 (pp. 233-241). Springer, London.