Arthritis is an umbrella term for more than 100 medical conditions that affect the musculoskeletal system, particular joints, which is the site where two bones meet.

The most common form of arthritis is Osteoarthritis (OA) and is a leading cause of pain, inactivity and disability. What’s concerning is that the prevalence and burden of OA is increasing. It’s typically known as an ‘óld person’s disease’ but OA does not discriminate, with the prevalence increasing sharply from the age of 45.

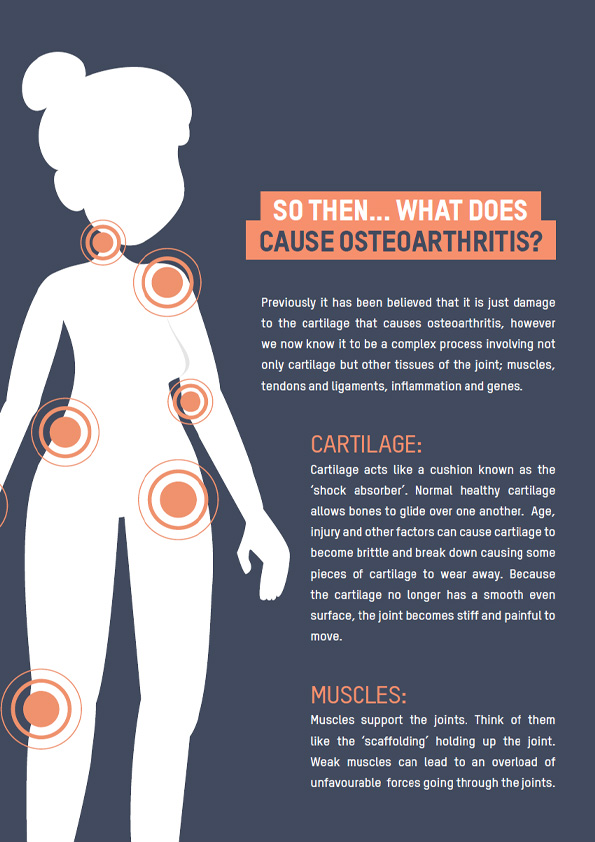

In the past, osteoarthritis has been referred to as “degenerative joint disease” and often comes with the phrase ‘wear and tear’ to the joint, however, we now know this to be a misnomer. OA is not simply just a process of wear and tear but is in fact a result of abnormal remodeling of the tissues within a joint that is driven by a cascade of inflammatory mediators – basically the joint trying extra hard to repair itself! Osteoarthritis can affect any joint but primarily affects the knee, hands, and hips.

Some people can have OA and not be aware, whereas others can have it and experience debilitating symptoms.

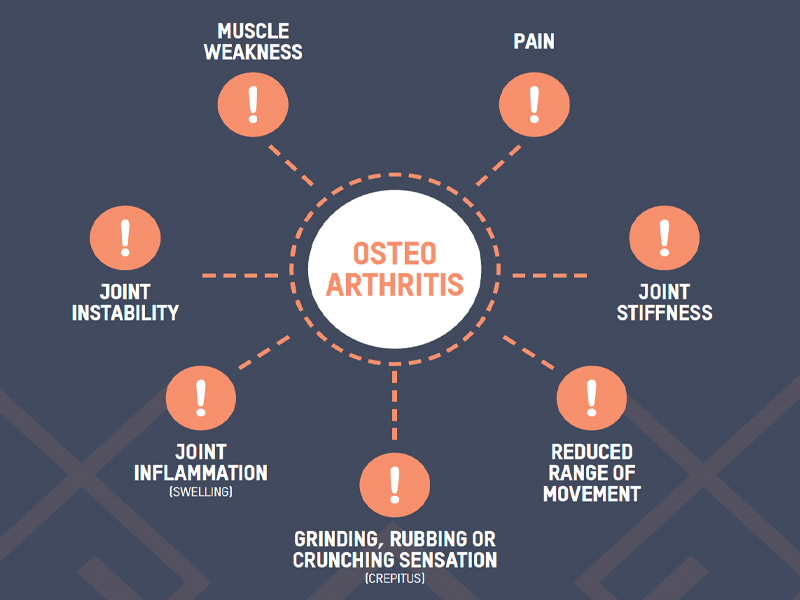

The main symptoms that are experienced with symptomatic OA include:

The thing with osteoarthritis is that it comes with an abundance of ‘facts’ that make understanding this disease and then knowing what to do REALLY challenging, so… let’s start with the myths, and then let’s go into more detail debunking them.

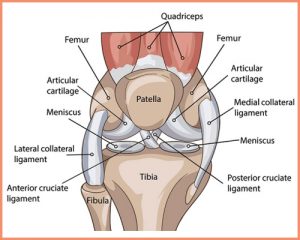

The knee is a hinge joint which consists of the thigh bone (femur), the shin bone (tibia) and the kneecap (patella). These bones are lined by a layer of cartilage and lubricating synovial fluid.

There are four main ligaments linking the femur and tibia;

• Medial (inner) collateral ligament

• Lateral (outer) collateral ligament

• Anterior (front) cruciate ligament

• Posterior (back) cruciate ligament

Two semi-circle rings of fibrocartilage known as ‘menisci’ are attached to and sit on top of the tibia, one on the medial side and one on the lateral side. They act as shock absorbers and distribute force evenly during impact and loading movements – such as walking, running and exercising. They deepen the articular surface of the tibia increasing the stability of the joint and also help to keep the femur in its correct position when the knee is bending.

The knee is involved in two main movements;

• Extension: produced by the quadriceps femoris

• Flexion: produced by the hamstrings, gracilis, sartorius and popliteus

And two secondary movements, which only occur when the knee is flexed (bent);

• Lateral rotation: produced by bicep femoris

• Medial rotation: produced by the semimembranosus, semitendinosus, gracilis and popliteus

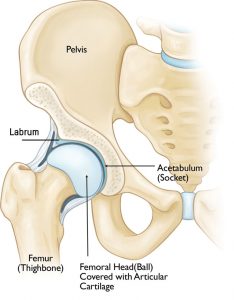

The hip is a ball and socket joint that connects the pelvic girdle to the lower limb. The socket is formed by the acetabulum which is part of the pelvis bone and the ball is the femoral head. The acetabulum cavity is deepened by the fibrocartilaginous collar – the acetabular labrum.

Articular cartilage covers the surface of the ball and socket which creates a smooth low friction surface that helps the bones glide across each other.

Synovium covers the surface of the joint which produces a small amount of fluid that lubricates the cartilage, aiding in movement.

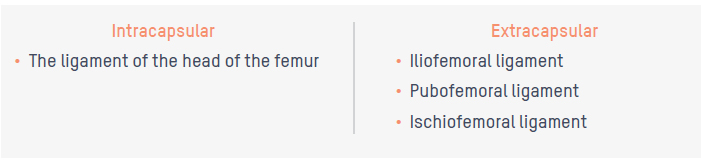

There are two groups of ligaments of the hip joint:

Due to the ball and socket nature of the hip joint it can perform a wide range of movements;

• Hip flexion and extension: moving the leg back and forth

• Hip abduction and adduction: moving the leg out to the side (abduction) and inward toward

the other leg (adduction)

• Rotation: pointing the toes inwards (internal rotation) or outward (external rotation)

Many people when experiencing pain will request imaging such as an MRI to determine the cause of the pain.

Imaging definitely has its place, however it’s important to understand that imaging doesn’t paint the whole picture.

A systematic review looking at 63 studies evaluated MRI’s of asymptomatic, uninjured knees – knees that had no history of known injury and were not causing any pain. It was found that:

Firstly, don’t be alarmed. All those things you hear about ‘bone on bone’ and ‘never being able to run again’ sound daunting, but there are ways to manage your symptoms to help you do what you enjoy. There are also many others in your shoes who continue to live fulfilling active lives.

There is no cure for OA however there are a multitude of treatment options that can effectively control your symptoms and help prevent further decline. You may have seen your GP who has advised you to manage conservatively or implement lifestyle changes before considering surgical interventions.

Conservative management is the management of arthritis without surgical intervention. There are many interventions that fall under this. It has been heavily researched that a combination of the below interventions are more effective than using one treatment alone.

The consensus from research and international guidelines recommends that the best first line of treatment for osteoarthritis management is the combination of weight management, exercise therapy and education.

There is then a range of adjunct therapies that can be considered to help with symptom management which includes:

• Medication/Supplements: paracetamols, NSAIDS, corticosteroid injections

• Heat and cold application

• Taping

• Massage/Manual therapy: mobilization, manipulation and dry needling

• Podiatry

• Braces/aids

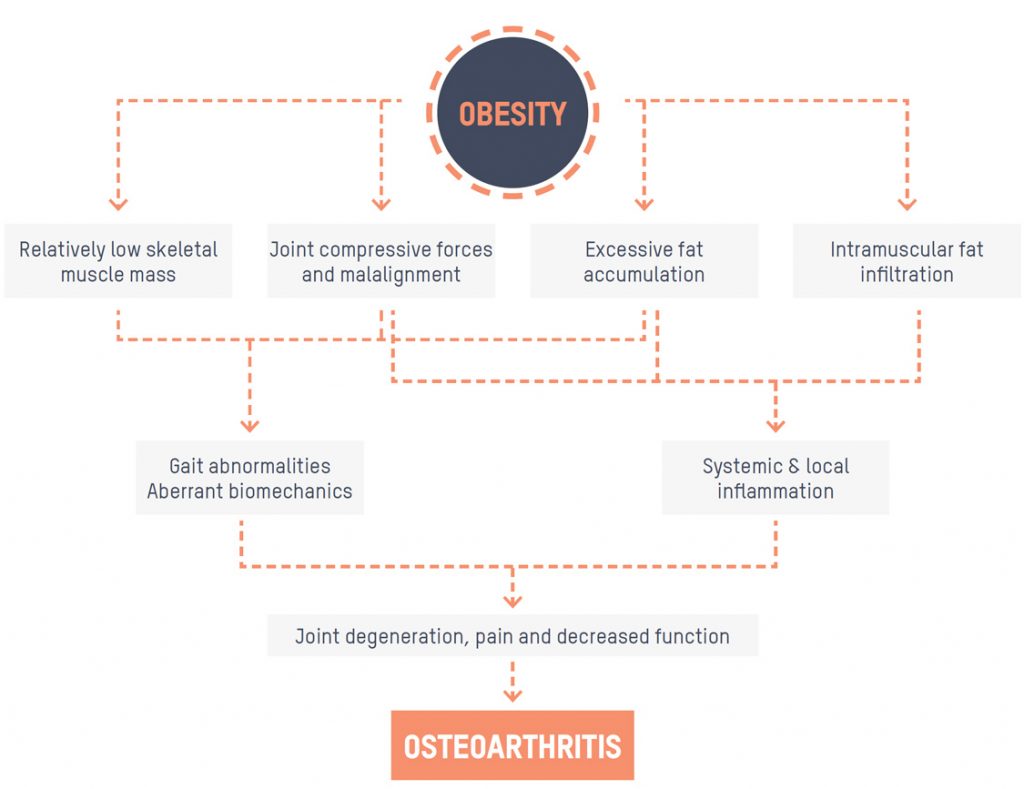

Obesity is a widely acknowledged risk factor for the incidence and progression of osteoarthritis. Not only is the global prevalence of OA continuing to escalate due to an ageing population, but also as a direct result of the current obesity

epidemic. To put this into perspective, every 5kg of weight gain increases the risk of developing knee OA by 36%.

Initially, the link between OA and obesity was considered purely biomechanical (the weight and the pressure on your joints increasing the likelihood/progression of the disease) however we now know that there are other factors to consider in this relationship.

We know this because although there is plenty of discussion surrounding the association between obesity and OA in weight-bearing joints (hips, knees), there is also a high prevalence of hand OA in those who are overweight or obese with the hand being a non-weight-bearing joint.

There are a few takeaways from this:

• An increase in body weight combined with a loss of muscle mass and strength means that the loads placed on the joints are too much for the joint to withstand.

• The mechanical stress on the joints can result in the release of proinflammatory mediators from joint tissues which impacts the progression of arthritis.

• Fat tissue releases molecules that contribute to levels of inflammation across the body in turn increasing the level of inflammation in the joint affected by OA.

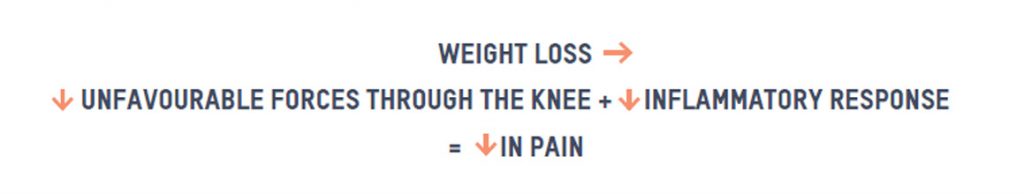

A study of overweight and obese older adults who experienced knee OA found that every pound lost resulted in a fourfold reduction in the load exerted on the knee per step during daily activities. Another study of 1410 individuals with symptomatic knee OA found a significant dose-response relationship exists between changes in body weight and changes in pain. So what we know is:

You may associate exercise with pain and feel concerned that it could harm your joints more, causing more pain. We get it, the mere thought of moving when your joints are feeling stiff, swollen and achy seems completely unrealistic. However, there is robust evidence for the effectiveness of exercise for the management of osteoarthritis and no evidence to suggest that it accelerates the progression of OA. It is actually considered the most effective, non-drug treatment for:

• Reducing pain

• Aiding in mobility

• Strengthening muscles that support the joints

• Improving physical function

• Optimising quality of life

In fact, a study published in the journal of Arthritis Care & Research looked at the impact of sedentary lifestyle (no activity) on quality of life in people with OA and found that “among 13.7 million persons with knee OA, a total of 7.5 million quality-adjusted life years were lost due to insufficient activity” (9).

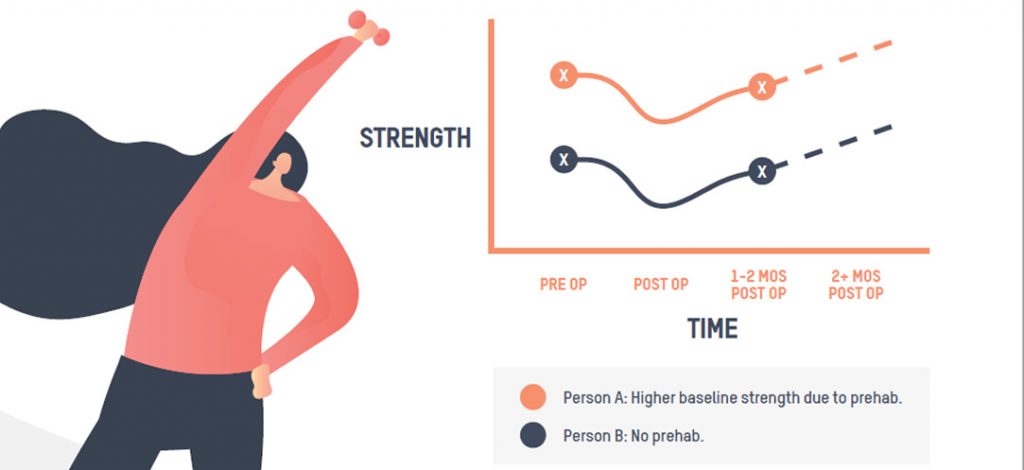

Starting an exercise program can delay the need for surgery which is why your GP may ask you to trial an exercise regimen and other lifestyle changes before considering surgical interventions. As mentioned earlier in the myths section, exercise also plays an important role in preparing you for surgery if that is the path you are going down. Having a higher baseline strength and endurance can mean that your post-operative recovery is a much smoother process for you. Improvements in post-operative function can be the difference between returning to work sooner, or getting back to your day-to-day activities faster.

We like to explain it to our clients that you want to give yourself the ‘best starting point’. We know strength directly impacts the function and overall joint health, so improving strength prior to your surgery set’s you up in the best possible position post-surgery.

The diagram below outlines this nicely. You can see Person A performed prehab and had a higher baseline strength meaning that there is a reduction in strength post-op. This is normal due to reduced use of the muscles supporting the joints in the short term. Their 1-2 month post-op strength was still higher than Person B who didn’t perform appropriate prehab.

Strengthening exercises have been shown to have the greatest long term effect on pain reduction and is typically the first-line treatment for arthritis management.

I previously likened the muscles to be similar to the scaffolding of the joint. Strengthening the scaffolding takes the pressure off the joints and helps with the overall function of the joint. Appropriate strengthening can also improve poor biomechanics that may be contributing to uneven forces on the joint.

Range of motion refers to the ability to move your joints through their full range. Stiffness and tightness are common symptoms of arthritis so adding gentle stretches and mobility exercises can relieve stiffness and help maintain normal joint motion. Weaker, stiffer joints tend to be more symptomatic and painful than mobile and strong joints.

This style of exercising improves the function of the heart and lungs, making them more efficient. Arthritis can often result in the development of other chronic diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease due to reduced physical activity therefore it is vital to include aerobic exercise to reduce the likelihood of disease progression. Aerobic exercise also plays a role in weight control by increasing the number of calories the body is using and as discussed before – weight management is one of the lifestyle changes.

The load that goes through the joints when weight bearing such as walking can be a really painful experience for some and make aerobic activity a really challenging exercise to incorporate into your regime. This is when we would include the Alter G anti gravity treadmill as part of your treatment plan. The Alter G uses differential air pressure to reduce body weight and thus forces going through the joints, making walking or other exercises far more tolerable. Alter G did a nice case study with a 71 year old patient who was reporting 5/10 pain levels for basic daily activities. By the end of her treatment which included the alter G treadmill, she was nearly pain free.

If weight-bearing is challenging for you, aquatic based exercise is a great option. The buoyancy of the water helps relieve the pressure of your body’s weight on the affected joints – it can unload almost 90% of your body weight! Water-based activity also acts as a great option for resistance exercise, think of walking 5 meters on land compared to 5 meters in the pool. The water places up to 12 times greater resistance than air, challenging the muscles to a much greater degree.

Yoga and Tai Chi are a great low impact exercise option to include in your exercise regimen to complement your strength training. The combination of moving, mindfulness, stretching and breathwork have been shown to help with pain management and improve overall well being.

As a rule, all adults should be aiming to do at least 30 minutes of activity every day of the week for all over health benefits. Research suggests just 150 min per week of moderate-intensity physical activity is associated with improved long term function in OA symptoms.

We understand that this can sound like quite a daunting amount to begin with especially if you are limited with what you can do because of pain. This is why we take a thorough history and work with you to create the most achievable plan that is suitable for your goals. It may be that you start with 10 minutes a day. That 10 minutes a day may eventually work towards 10 minutes three times a day.

Weight-bearing exercise can come with its challenges, so we might prescribe a session on the alter G treadmill one day, a session in the rehab gym a few days following and then a hydro session a few days after to finish off the week.

Living with pain can be one of the most challenging aspects of arthritis. Research has shown that understanding how pain works and how you can respond to it can help prevent pain from controlling your life. Our minds play an important role in how we feel pain and can be affected by our stress levels, fatigue, emotional and mental wellbeing. Pain generally provokes an avoidance of exercise which compounds the problem of deconditioning. Avoidance because of the pain is inadvertently making those muscles that control the joint and make it more stable, weaker. We call this the pain cycle:

Pain may limit what you do, but it doesn’t have to control your life. So, when you exercise, how do we use pain to determine our loading? We generally go off a “two-hour pain rule”. If you have extra or different pain for more than two hours after exercising we take this as a sign that too much has been done. This doesn’t mean you should stop exercising outright. You’ll have a day or two of rest and then continue at a slightly lower level of intensity. Eventually, with increases in strength and joint mobility, your exercise tolerance will be higher than when you started.

There is no specific time of day that you should exercise, the main goal is to just exercise. Try and plan your exercise sessions around:

• The time of day you experience less pain

• The time of day you are least stiff

• The time of day your medications are most effective

Planning your exercise around the above points will help make the exercise session more comfortable for you.

Depending on your symptoms, your doctor may advise medication. The most common types used to treat OA include:

• Pain relievers or analgesics: such as paracetamol for temporary pain relief

• Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDS): such as ibuprofen reduce inflammation which can then reduce pain and swelling.

• Anti-inflammatory or analgesic creams and gels: may provide temporary relief

• Steroid injections: such as Cortisone injections are sometimes recommended to those with significant pain after trying other methods of pain management such as weight loss, exercise and other medications. However, steroid injections shouldn’t be given repeatedly and no more than 3 to 4 a year as it can cause damage to the tendons, ligaments and articular cartilage.

The benefits of heat and cold application are yet to be proven by research however these treatments are soothing and many people report improvements in pain and joint stiffness following the use.

Thermo therapy (Heat): Heat relaxes the muscles and stimulates blood circulation and can be applied via wheat packs, towels, warm water or sometimes wax. Some people find the application of heat such as a wheat pack to the joint prior to exercising to relax the muscles and get the blood flowing can be beneficial in ‘warming the joint up’. This can also be used in cooler months when getting out of bed in the morning can be stiff and sore.

• Cryotherapy (Cold): Cold application reduces swelling and inflammation. Applying an ice pack to the painful area for 15 minutes during a ‘flare-up’ may be useful.

• Hot and cold combination can be helpful for pain management. For example, using a heat pack prior to exercising and then an ice pack following to help relieve any pain.

Massage involves the manipulation of soft tissues in the body using pressure, tension, motion or vibration. There is limited scientific studies on the benefits of massage specifically for arthritis, however, massage can improve circulation and reduce swelling which can help with pain relief in the joints. Massage may also temporarily improve the mobility of the joints.

Podiatrists will assess lower limb biomechanics and may prescribe the use of orthosis. There has been evidence to show that custom foot orthotics can help reduce pain.

The use of an aid such as a walking stick or cane will help offload the affected painful joint and therefore help manage the symptoms. Some individuals may be fitted with an unloader brace which works to offload the knee joint by applying corrective forces to the leg to take the pressure off areas where the arthritis is at its worst and transferring to the unaffected parts of the knee. Other devices such as jar openers, reachers, easy grip utensils and shoe horns can help keep the joint in the best positioning for functioning, provide leverage when needed and can extend range of motion, helping with daily tasks that are made challenging due to pain.

There comes a time when surgery might be an option to consider. The following list is a good guide to determine if it is appropriate to talk to your GP about the possibility of surgery:

• If your pain has not improved with other treatments such as weight control, exercise or medication.

• The arthritic joint is making it impossible for you to look after yourself and complete everyday tasks such as showering, getting dressed, making meals.

• Your pain is so severe that you are finding it difficult to work or it’s keeping you from doing the things you love.

After you’ve had the discussion with your GP, they will refer you to an orthopaedic surgeon such as Melbourne Hip & Knee who will do a thorough assessment and make a recommendation depending on your presentation and symptoms.

It is important to have an open discussion with your surgeon and have an understanding of:

• The benefits of the surgical option

• The risks of the surgery

• If there are any other options

• What would happen if your surgery failed?

Arthroscopic Debridement and Washout:

Arthroscopes is often called ‘keyhole’ surgery or a knee scope and is undertaken to remove and ‘clean up’ concerns such as cartilage flaps, degenerative meniscus tears or any loose bodies. An instrument (arthroscope) is put into the joint and allows the surgeon to see the condition of the joint and proceed with any operative intervention required. The effect of arthroscopy tends to be temporary but can last many months to years.

Osteotomies:

This involves the surgical breaking of bones with the aim of realigning the mechanical axis of the limb.

Unicompartmental Replacement or Partial Replacement:

Arthritis in the early stages can involve only one compartment of the knee such as the medial compartment, the lateral compartment or the patellofemoral compartment. If symptoms are only isolated to one compartment it is a more viable option to treat that area.

The advantages of unicompartmental knee replacement include:

• Less invasive

• Quicker recovery period.

• Preserves bones and ligaments

Total replacement:

Total replacement of the joint is a suitable option for those individuals who are at the end stage of arthritis or have tried other methods of management and haven’t seen any improvements in pain and who struggle completing day-to-day tasks.

It is important to note that joint replacement is an excellent option for many patients but does not last forever and may need a revision in the future. A systematic review and meta-analysis of case series, cohort studies and Australian and Finnish registries (36 481 total knee replacements, 8456 unicompartmental knee replacements and 228 888 hip replacements) determined the survival rate is up to 25 years. (6) It is for this reason that many patients try and use conservative treatment options to delay the joint replacement process.

Do you need help from an Exercise Physiologist?